More anarchist stuff from Indonesia

Gloria Truly Estrelita, Jim Donaghey, Sarah Andrieu and Gabriel Facal – A Brief History of Anarchism in Indonesia

[Also available to read in Bahasa Indonesia, and as an audio podcast in both English and Indonesian at Anarchist Essays]

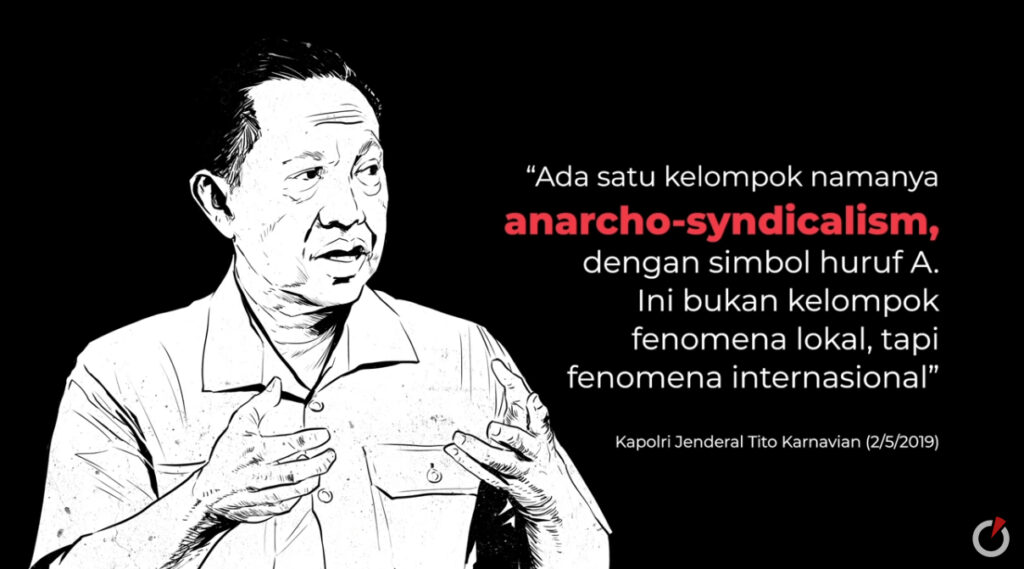

In the Indonesian language, the term ‘anarki’ is synonymous with the riotous behaviour of a disparate range of groups, including everything from Islamic fundamentalists to football fans. The state has played a role in shaping this popular discourse of anarchy-as-chaos, including in their establishment of an ‘anti-anarchy’ police division in 2011, which actually targeted rioting by religious mobs (this police division was itself an implementation of the Indonesian state’s Procedural definition of ‘anarki’, see their ‘Prosedur Tetap (Protap) Anti Anarki’ of October 2010 (Lastania et.al 2010)). In more recent years, the state has shifted its discourse to identify anarchism as a form of populist terrorism, with purported links to communism – which remains highly taboo in Indonesia and, in its Marxist-Leninist guise, is still officially proscribed by the state (Guritno 2022). The authorities use the term ‘anarko-sindikalis’ to differentiate this form of anarchism from the ‘anarki’ of other rioters, and groups identified as such suffer persecution. This contemporary scenario, and the longstanding ‘red scare’ in Indonesia, means that speaking out on the anarchist movement remains delicate.

Anarchism in the context of anti-colonialism and nationalism in Indonesia

Far from the stereotypes that are conveyed, the anarchist movement in Indonesia is made up of diverse groups with various ideas and practices. Analysts of political life in Indonesia observe that pragmatic issues often override ideological considerations (Rosanti 2020). Political parties and trade unions organise themselves in terms of religion, regionalism, or ethnic identity, relying on pre-established societal networks. Indeed, despite the democratisation reforms after the fall of the Suharto regime in 1998, engagement in any form of progressive politics is suspected of being Socialist-oriented, and is closely monitored by the intelligence agencies and their local civilian supporters (Honna 1999: 121).

This was not always the case. During pro-independence struggles in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, anarchism was influential on anti-colonial thinking, arriving in Indonesia alongside the upswell of communism and nationalism under the regime of the Dutch East Indies (Satria Putra 2018; Nugroho 2021). The first book to describe ‘anarchistic’ tendencies in the Dutch East Indies was the novel Max Havelaar, written by Eduard Douwes Dekker under the name ‘Multatuli’ in 1860. The book strongly criticised the Dutch East Indies colonial government, and the work inspired many anarchists (Satria Putra 2018). Multatuli’s struggle was then continued by his grandson, Ernest François Eugène Douwes Dekker, who linked up with radicals struggling for the liberation of the colonies while on a trip to Europe in the early 1910s.

During World War One, in 1916, the Dutch East Indies newspaper Soerabaijasch Nieuwsblad reported on a sabotage led by a young anarchist navy soldier (Blom 2004). This resonated with the prolific anti-war propaganda works of the time, which in the Dutch East Indies was chiefly disseminated by Christian-anarchists and Tolstoysans (it is notable that E.F.E. Douwes Dekker himself described Jesus Christ as a fighter for freedom and ‘a great anarchist’ (Van Dijk 2007)).

The anarchist movement in the Dutch East Indies was also influenced by Chinese anarchists in the years before the First World War, and Indonesia-based activists maintained close contact with anarchists in China, the Philippines, and British Malaya. The Chinese anarchist movements established reading houses all over the Dutch East Indies from 1909 onwards, which published numerous newspapers and became a loose political association opposing the Dutch authorities.

Anarchist ideas also caught the attention of several young Indonesian students in the Netherlands, who later developed contacts with local Dutch anarchists. Among them was the first prime minister of the Republic of Indonesia, Sutan Sjahrir (Damier & Limanov 2017, Mrázek 1994). These young students established links with left-wing political forces and took part in the work of the International League Against Imperialism and Colonial Oppression, or also known as the World Anti-imperialist League (Satria Putra 2018).

With echoes of the contemporary situation in Indonesia, the colonial government used the anarchist label to arrest those who criticized the government. For example, in 1927, the Dutch authorities arrested several members of Sarekat Ra’jat (formerly known as Sarekat Islam Merah, or Red Islamic Association), who were found guilty of the charge of anarchism, and subsequently banished to West Papua (Suryomenggolo 2020).

From the 1920s onwards, the Communist Party of Indonesia (in Indonesian language, Partai Komunis Indonesia or PKI) exerted its influence at the local level, solidifying a strong popular base, especially after Indonesia’s declaration of independence in 1945. It was one of the big winners in the first general election of 1955, and by the 1960s grew to become the third-largest communist party in the world with three million members, plus a constellation of satellite grassroots organisations (Lev 2009). After becoming aware of the covert involvement of the United States and the United Kingdom in the revolts of 1957-1961 (Conboy and Morrison 2018) and their meddling provocation of the Indonesia-Malaysia confrontation of 1962-1966 (Wardaya 2008), the nationalist President Sukarno came to support the PKI’s anti-Western position. In the wider context of the Cold War, this led other political parties, right-wing army leaders, and Western governments, to fear that the communists were taking over the country.

But while Sukarno embraced some Leftist groups, he was not sympathetic to the anarchist movement (even despite his habit of quoting the anti-colonial writings of Mikhail Bakunin during his speeches (Danu 2015)). Earlier in Sukarno’s political career, in 1932, he published an article titled ‘Anarchism’ in Fikiran Ra’jat (or People’s Thought ) daily, the newspaper of the Indonesian Nationalist Party (the PNI). In it, Sukarno expressed his opposition to the anarchists and their rejection of the state and patriotism. While he could agree with the anarchists in their fight against colonialism, Sukarno was a nationalist and a statist first-and-foremost.

Anarchist thought had a wide-ranging influence. Even the avowedly Marxist-Leninist PKI featured quotes from Bakunin in the editorials of their Koran Api journal in the 1920s – though the author, Herujuwono, a Party Chairman in Central Java, was scolded by Darsono, a PKI founder, in 1926 for muddying the Party’s ideological purity. However, this episode does highlight the considerable heterogeneity of the Left in Indonesia, with significant cross-pollination of ideas across political milieus under the overarching anti-colonial struggle (Satria Putra 2018).

The repression of the Left, and anarchism’s re-emergence

The tragedy of 1965-1966 brutally curtailed the political trajectory of the PKI and other leftist groups in Indonesia. On September 30, 1965, in response to the assassination of high-ranking army officers, the military under Major General Suharto took control of the country, accusing the PKI and its affiliates of responsibility for the assassination plot. The most significant anti-communist purge in modern Indonesia was launched on an archipelago-wide scale. In 2016, the International People’s Tribunal set a consensus estimate of 500,000 people killed during the atrocities (IPT Report 65 2016).

As soon as it seized power, General Suharto’s New Order regime demonised communism in its propaganda and prohibited Leftist philosophy, politics and imagery (Estrelita 2010). In a country where religion was compulsory and directly associated with political power, the conflation of communism with atheism had a powerful effect. State institutions and the people themselves were involved in daily repression that turned Indonesia into an anti-communist surveillance society.

After thirty years of repression and marginalisation under this wide ranging ‘red scare’, anarchist activism re-emerged in the 1990s. Its revitalisation was fostered by student movements across the archipelago and particularly by punk counter-culture (Satria Putra 2018; Anjani 2020). At that time, anarchism was synonymous with punk – the punk community learned about anarchism through the lyric sheets of anarchist-engaged punk bands, and through punk-anarchist zines from the US and Europe, which were transported to Indonesia by travelling punks, and then copied and re-distributed, and translated in locally produced zines (Donaghey 2016). The discourse of anarchism diversified in the ensuing years, influencing activists, students, and workers, and eventually reaching a wider society with diverse backgrounds.

During the political upheavals against the New Order regime in the late 1990s, many anarchist sympathisers claimed membership of Anti-Fascist Front (Front Anti-Fasis, FAF), which was founded in 1997 in Bandung, bringing together punks, street kids [anak jalanan] and petty thugs [preman]. Some FAF members joined the socialist People’s Democratic Party (or PRD) in 1999 (F Putra 2022), but this was a disappointing experience for the anarchist-minded activists, and the opinion of those who had kept their distance from the PRD was vindicated – they had argued all along that entry into party politics led to co-optation and the stifling of critical speech (anonymous interviewee 2022).

Even within this alliance, FAF supporters autonomously continued their underground activism. In December 1999 and February 2000, they met with punk groups in Yogyakarta and formed the Jaringan Anti Fasis Nusantara (JAFNUS, or Archipelago-wide anti-fascist network), which was subsequently suppressed by the Gerakan Pemuda Ka’bah (or GPK) civil militia, who accused the activists of being communists (anonymous interviewee 2022).

A later effort to consolidate anarchistic groups within a network saw the creation of the Jaringan Anti-Otoritarian (JAO, or Anti-Authoritarian Network) in 2006 (F Putra 2022). In addition to its role as a rallying point for large-scale May Day demonstrations in 2007 and 2008 (the latter of which was severely repressed by the police), and the introduction of black bloc tactics and aesthetics, the JAO federation linked together the intersecting struggles of anti-authoritarianism, anti-capitalism, anti-statism, non-sectarianism, non-religious revivalism, anti-racism, federatism, autonomy, and ecology.

From subsequent struggles and inter-group meetings, the Workers’ Power Syndicate formed in 2014, leading to the establishment of the Anarcho-Syndicalist Workers’ Brotherhood (Persaudaraan Pekerja Anarko Sindikalis, or PPAS) in 2016 – it is the first anarcho-syndicalist organisation in Indonesia since the fall of the New Order. They took part in the massive May Day protests of 2018 and 2019 (F Putra 2022), and the protests against the so-called ‘Omnibus Law’ labour reform bill in 2020, contributing to riots that drew the media spotlight and renewed police attention.

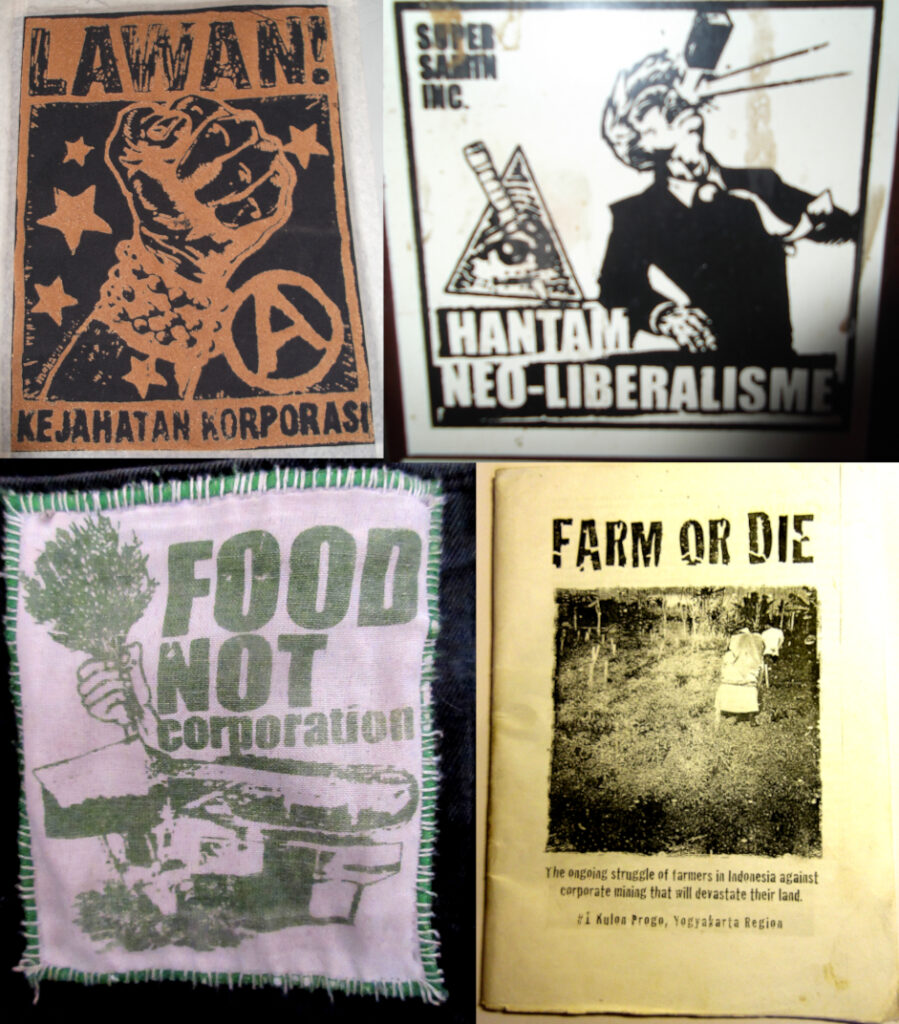

Within and beyond these evolving groups and networks, anarchists have been engaged in a wide range of activisms, including: running infoshops; publishing books, pamphlets and zines; engaging in solidarity actions with local communities; boycott and sabotage actions; demonstrations and black bloc actions; and artistic performance interventions. Important fractions of the movement are involved in community support for urban laborers, rural peasant communities, or populations suffering land grabs and ecological degradation. The proliferation of itinerant libraries (or perpustakaan jalanan), which developed from 2009 in Bandung and have spread elsewhere, highlights the focus on education. These libraries also provide free food, via public kitchens (or dapur umum) organised under the Food Not Bombs banner (Damier and Limanov 2017). The Anarkis.org website, founded in 2014, also serves as a vital resource for self-education and critical discussion within the movement.

Anarchist groups in Indonesia are marked by vernacular specificities, such as the concept of family-ism, and its particular dynamic of hierarchical interpersonal relations. This structural dimension shapes the dialogue between mobilised communities and anarchist groups, who are obliged to negotiate certain power relations. The prevalence of religion and the link to spirituality are also resources of mobilisation for some anarchists. In a country where atheism is unaccepted, many movement members practice religion, and Indonesian anarchists tend to be more flexible than their European comrades – often recognising the anarchist ‘No Gods, No Masters’ ideal, while also assisting religious minority groups, like the Shia or Ahmadi people (anonymous interview 2022).

Examples of mutual aid (known locally as gotong royong), horizontal solidarity, and autonomy, are numerous among the traditional cultures of the Indonesian archipelago, although this was not labelled ‘anarchism’, of course. Indigenous communities, like the Samin people, Kajang, Dayak, Tanimbar, or Kanekes, are conceived as embedding these anarchistic practices through their collective way of life and retreat from, or resistance to, the State. In this perspective, it is not anarchism that was imported from abroad, but the State itself. These interpretations are enriched by interactions between anarchists and the inspiring traditional communities.

Anarchism under repression, and the significance of contemporary anarchist critiques

Today, after 60 years of nationalist and anti-communist propaganda, and despite the return of democracy in 1998, progressive ideas are harshly repressed as a potential resurgence of the spectre of communism. This has been the case with the large-scale popular mobilisations that have been multiplying since May 2019 in protest against the politics of money, corruption, and authoritarianism. The current red-scare label-of-choice is ‘anarcho-syndicalism’, presented as a morally deviant and conspiratorial nebula that threatens public order (Maharani 2019). In 2019, police authorities declared anarcho-syndicalists responsible for May Day riots in several major cities. During the Covid-19 pandemic, the national police announced that anarcho-syndicalists had organised attacks on public facilities across Java (Velarosdela 2020; Anjani 2020). As a result of this stigmatisation, several city authorities now even declare their rejection of the movement on publicly erected banners (Nugroho, 2016).

The anarchist movement appears today as the last vocal Leftist political movement in Indonesia, although it remains a weak voice in a political landscape dominated by the traditional parties linked to oligarchies, religious organisations, and business consortiums. The two terms of the current president, Joko Widodo, have further marginalised progressive ideas, increased inequality, reinforced the power of the military, and made little effort to counter environmental catastrophe. But anarchist analyses are particularly well-placed to articulate the systemic dimensions that underpin contemporary Indonesian society, and their voice is vitally important as a result.

References

Anjani, Kirana. Kaus Hitam dan Paranoia Negara: Stigmatisasi dan Pelanggaran Hak Kelompok Anarko-Sindikalis. Indonesia: Lokataru Foundation, 2020.

Blom, Ron, & Stelling, Theunis. Niet voor God en niet voor het Vaderland. Linkse soldaten, matrozen en hun organisaties tijdens de mobilisatie van ’14-’18. Amsterdam: Aspekt, 2004.

Damier, Vadim & Limanov, Kirill. ‘Anarchism in Indonesia’. libcom.org, 14 November 2017. https://libcom.org/article/anarchism-indonesia-0

Danu, Mahesa. ‘Bung Karno Dan Anarkisme’. Berdikari Online, 16 March 2015. https://www.berdikarionline.com/bung-karno-dan-anarkisme/

Donaghey, Jim. Punk and Anarchism: UK, Poland, Indonesia [PhD thesis]. UK: Loughborough University, 2016. https://repository.lboro.ac.uk/articles/thesis/Punk_and_anarchism_UK_Poland_Indonesia/9467177

Estrelita, Gloria Truly. Penyebaran Hate Crime oleh Negara Terhadap Lembaga Kebudayaan Rakyat [Master’s thesis]. Jakarta: Universitas Indonesia, 2010.

Final Report of the IPT 1965. https://www.tribunal1965.org/en/final-report-of-the-ipt-1965/

Guritno, Tatang. ‘Menyebarkan Komunisme, Marxisme, Leninisme Dapat Dipidana, Koalisi Masyarakat Sipil: Menghidupkan Orde Baru’. KOMPAS.com, 5 December 2022. https://nasional.kompas.com/read/2022/12/05/19061841/menyebarkan-komunisme-marxisme-leninisme-dapat-dipidana-koalisi-masyarakat

Honna, J. ‘Military Ideology in Response to Democratic Pressure during the Late Suharto Era: Political and Institutional Contexts’. Indonesia, 67, pp. 77-126, 1999.

Lastania, Ezther, Riky F & Jobpie S. ‘Polisi Miliki Protab Baru Anti Anarki’. tempo.co, 10 October 2010. https://metro.tempo.co/read/283651/polisi-miliki-protap-baru-anti-anarki

Lev, Daniel S. The Transition to Guided Democracy. UK: Equinox Publishing, 2009.

Mrázek, Rudolf. Sjahrir: Politics and exile in Indonesia. New York: Ithaca, 1994.

Nugroho, Pujo. Kota Merah Hitam. Indonesia: Solidaria.id, 2021.

Putra, Bima Satria. Perang yang Tidak Akan Kita Menangkan: Anarkisme dan Sindikalisme dalam Pergerakan Kolonial hingga Revolusi Indonesia (1908-1948). Indonesia: Pustaka Catut, 2018.

Putra, Ferdhi F. Blok Pembangkang: Gerakan Anarkis di Indonesia 1999-2011. Indonesia: EA Books, 2022.

Rosanti, Ratna. ‘Political Pragmatics in Indonesia Candidates, the Coalition of Political Parties and Single Candidate for Local Elections’. Jurnal Bina Praja, vol. 12, no. 2, 2020.

Suryomenggolo, Jafar. ‘Dari Sekolah Liar Hingga Anarkisme’. Historia, 23 May 2020. https://historia.id/politik/articles/dari-sekolah-liar-hingga-anarkisme-PG89B

Van Dijk, Kees. The Netherlands Indies and the Great War, 1914-1918. The Netherlands: Leiden. 2007.

Velarosdela, R. N. ‘Polisi Selidik Dalang Kelompok Anarko yang Berencana Lakukan Vandalisme Massal’. Kompas, 13 April 2020. https://megapolitan. kompas.com/read/2020/04/13/18103381/polisi- selidik-dalang-kelompok-anarko-yang-berencana- lakukan-vandalisme

Wardaya, Baskara T. Indonesia Melawan Amerika Konflik PD 1953-1963. Yogyakarta: Galangpress, 2008.

Dominic Berger – Indonesia’s new anarchists

Insurrectionary anarchists, with international connections, nihilist values and a penchant for arson, are moving to fill the vacuum on the left

par Dominic Berger

On the night of 22 March 2011, bricks smashed the windows of a McDonald’s branch in Makassar. A note was left by the attackers : ‘We are aware of what you multinationals have done to the people of Kulon Progo, Takalar, Bima, and other places. We are angry and we’ll do more !’ Naming places where farmers have resisted large mining projects, the note and the smashed windows seemed to be an expression of local grievances. Three days later, police in Makassar found a note near a scorched ATM owned by BCA (Bank Central Asia) : ‘We don’t want to hurt anyone, destruction of property is not violence ! The state, the military, police and capitalists are the real terrorists !’ The note was signed by a group calling itself the ‘Got is Tot (sic) [God is Dead, in German] Insurrectionary Front’.

It seems likely that police investigators in Makassar missed the Nietzsche reference, but even without a grasp of anarchist philosophy, the radical political motivations of this direct action were not lost on the provincial police force. ‘The perpetrators set fire to the ATM to incite terror’, a police spokesperson was quoted as telling the media. ‘They broke into the ATM machine and left a letter carrying their message of terror’.

Two weeks later, another BCA ATM was burned in Manado, North Sulawesi. Notes were found in which the ‘International Conspiracy for Revenge’ claimed responsibility. ‘We have become sick and tired of all the standard methods that are never listened to. There is no more reason to remain passive and not counter-attack. This is WAR !’ Two months later, in June 2011, police found notes scattered near a torched BNI (Bank Negara Indonesia) ATM in Bandung, with an almost identical message to the Makassar and Manado attacks that concluded, ‘with this statement we claim to join the FAI [Informal Anarchist Federation], Indonesian Section.’ Insurrectionary anarchism had arrived in Indonesia.

Since the fall of the New Order, anarcho-punk collectives, such as Marjinal and Taring Babi, have become the public face of anarchism in Indonesia. Mostly poor, urban youths flock to these communities in cities like Jakarta, Bandung and Yogyakarta, and anarchist ideas are buried beneath the punk fashion, music and mild social activism they promote. However, for serious anarchists the Indonesian anarcho-punk scene has become far too mainstream. ‘Bandung is not like it used to be. The punk-scene became commercialised and everyone ‘sold out’’, complains one non-punk anarchist. Designing distro (independent label) shirts and throwing concerts in Bogor is simply not the kind of stuff that will bring down the system.

A new breed of Indonesian anarchists views the punk scene as little more than a harvesting ground ripe with angry youths partially socialised into anarchist ideas and symbols. As one such anarchist activist told me, ‘most punks are useless, but punk communities provide anarchism with a cultural base which Marxism has lacked since 1965’. While social stigma and an ongoing ban leave Marxism still too hot for the masses, to the rebellious punk-kid, Das Kapital is already stale, something belonging in the 1960s. Anarchism, on the other hand, is exciting, anti-authoritarian, and legal. Those who want to lose the mohawk and get serious about resistance to state and capital can find a guiding hand from more experienced anarchist ideologues who routinely exhibit tables full of alluring anarchist literature to crowds of anarcho-punks at concerts around Indonesia. But increasingly the ideological inspiration comes from further afield.

Indonesia arrives on the global scene

Insurrectionary anarchism arose out of Italy’s vibrant anarchist scene three decades ago. Cells sprang up around the Mediterranean during the early 1990s, and later globally, on the back of the anti-globalisation ‘black bloc’ movements. The designation ‘Informal Anarchist Federation (FAI)’ has been used since the early 2000s by autonomous cells throughout Europe to identify adherence to a particular form of anarchism that explicitly rejects classical anarchism and Marxist-inspired forms of resistance. But it was the financial crisis that hit Greece in 2008 that blew new life into the movement, all the way to Indonesia.

The FAI and similar groups consider any attempts at organisation, reform or movement-building as counter-productive. When Indonesians protested against the planned reduction of fuel subsidies in June 2013, an Indonesian cell of the FAI issued a communiqué stating that ‘we are not at all interested in becoming involved in the wave of mass protest against fuel price hikes.’ The group posted its statement on an Indonesian language anarchist blog, but within days it was translated into English and posted on the international counter-information blog 325.nostate.net. The statement condemned as cowards ‘those who took to the streets carrying banners and shouting, performing repetitive and predictable actions, hiding in the terminology of “peaceful protest” to hide their inability to attack the oppressors.’

Instead of organisation, insurrectionary anarchists favour ‘direct action’ as their method, meaning arson, sabotage, and mailing letter bombs. Anarchists in Indonesia have so far been much tamer than their European counterparts, but events in recent years suggest that at least some of Indonesia’s anarchists are eager to lose their innocence.

Billy and Eat

The attention gained by the torching of ATMs in Makassar, Manado and Bandung, stirred into action two aspiring anarchists named Billy Augustian and Reyhard Rumbayan (known as Eat). In October 2011 the pair poured two bottles of petrol into a BRI (Bank Rakyat Indonesia) ATM in Yogyakarta’s Sleman district, setting it alight and destroying it completely. As one of them ran away from the scene, he dropped his wallet and a bag containing incriminating communiqués. Both were arrested within hours.

In court documents, Sleman’s public prosecutor argued that 30-year old Billy and his accomplice, Eat, decided to burn the ATM in Yogyakarta after they were inspired by how the Bandung ATM attacks had drawn attention to the human rights abuses, environmental destruction and capitalist exploitation in Kulon Progo, a land conflict site that has become a cause célèbre for anarchists. But the similarity between the notes left behind in Bandung and Makassar, and those found in Billy and Eat’s bags, along with the fact that Billy is a native of Bandung, suggest a closer connection than mere inspiration.

At first it seemed as if local grievances were the main motives of the series of ATM torchings. The notes Billy and Eat had prepared contained threats against PT Jogja Magaza Iron, a mining company active in Kulon Progo, a district west of Yogyakarta. Since 2005 the Paguyuban Petani Lahan Pentai Kulon Progo (Kulon Progo Seashore Peasant Collective) a self-described ‘informal collective’ of famers has, sometimes violently, opposed plans for a mining project in the region. The collective is hostile to all outside interference from NGOs and leftist organisations, including the high profile and widely-respected Legal Aid Institute (LBH). Their position papers circulating online are heavily tinged with anarchist vocabulary and since 2007 anarchist groups have openly worked in solidarity with the collective. It is possible that the ATM attacks were at least inspired by this collective, if not stemming directly out of its milieu.

Despite these local grievances, the insignia on Billy and Eat’s communiqué made it clear that they were linked to international anarchist networks. New FAI cells adopt names of fellow anarchists, usually of those in jail for their direct actions, as a sign of solidarity. In June 2011 Chilean anarchist Luciano Tortuga was jailed after he lost both his hands when a bomb he was placing near a bank exploded prematurely. Chilean anarchists put out a ‘call for solidarity’ that quickly spread around the anarchist blogosphere. FAI cells around the world sprang into action, smashing windows of a bank in Bristol, and destroying ATMs in Milan. But the greatest act of solidarity for Tortuga came from Indonesia, where Billy and Eat named their cell the ‘Long Live Luciano Tortuga’ Cell of the Informal Anarchist Federation-International Revolutionary (FAI/IRF). Their arrest was about to make them the poster-boys of the global community of insurrectionary anarchists.

Laying charges under the 2002 Anti-Terrorism Law, public prosecutors of Yogyakarta’s Sleman district defined the destroyed BRI ATM as a ‘strategic object’ and argued that by destroying it, Billy and Eat had ‘deliberately used violence with the intention of creating a sense of terror and widespread fear amongst the general public’. Eventually both were sentenced to a lesser charge of arson and jailed for one year and eight months, but the arrest and charges of terrorism had already catapulted Billy and Eat into the spotlight of the international anarchist scene.

In May 2012 the walls of the Indonesian embassy in Manila was splattered with black paint. Leaflets strewn in the area demanded ‘freedom to Eat and Billy, freedom to the victims of state repression, stop the environmental destruction, Indonesian state is the real terrorist’. In June 2012, Tortuga – the Chilean anarchist Billy and Eat had named their cell after – posted a note reflecting on his physical disfigurement and his imprisonment, thanking his ‘dear friend Reyhard Rumbayan (Eat), who with his noble gestures has brought me strength when I was weak’. By late 2012 a 27-page brochure profiling the two ‘urban guerrillas from Indonesia’ was circulating on blogs. It included letters of praise from other militant anarchist movements, trial updates, letters and poems written by Billy and Eat from prison, and details of solidarity attacks carried out internationally and in Indonesia.

Renewal in Sulawesi

But the ‘Long Live Luciano Tortuga’ cell was bigger than Eat and Billy. In August 2012, when the pair were in prison, a cell of that name was active in North Sulawesi. An incendiary device left behind by the cell failed to ignite at a power plant in Kotamobagu, around 100 kilometres from Manado. On the night of 31 August, the cell left another incendiary device at a local electricity station in the Manado suburb of Tuminting. In their communiqué, the cell sent their ‘greetings with the lights of fire from the streets to our two brothers in struggle, members of the Long Live Luciano Tortuga Cell FAI/IRF ; Billy Augustan and Reyhard Rumbayan (Eat).’

Despite claims of solidarity, tensions and divisions can be read between the lines of the Sulawesi cell’s communiqué. The statement concluded that ‘these actions are also a manifestation of anger and disappointment. Impatience for those rebels who after attacks returned to run and hide.’ Eat and Billy expressed similar feelings of abandonment in an open letter to the global FAI movement, written from prison one month after they were caught in late 2011. ‘We are truly disappointed that some of our local comrades are inspired by fear and media sensationalism which make them retreat from the front line.’

From these and other blog-posts written by Eat, it appears not everyone in the anarchist community agrees with the methods of direct action. Even those who carry out arson attacks have in statements indicated a rejection of deadly violence. For example, on Guy Fawkes Night (5 November –the date when Guy Fawkes and other conspirators in the Gunpowder Plot had planned to blow up England’s parliament at the start of the seventeenth century, recently commemorated by some anarchists) in 2012 the Sulawesi cell placed an incendiary device amongst luxury cars parked at Manado’s Red Monkey Karaoke Bar, pointing out in a communiqué that the device was placed deliberately away from possible human casualties.

Although Indonesia’s anarchists are still shying away from deadly violence, Eat and Billy’s imprisonment has placed Indonesia literally on the map of international insurrectionary anarchism (see photo). By November 2012, an Indonesian cell even took the initiative to issue an ‘international call for direct action against all property and symbols of society, eco-destroyers, fascists, military and our enemies.’ Three days later, the same cell claimed responsibility for setting alight an elementary school in Paniki, Manado. By January 2013, a FAI cell in North Sulawesi was claiming responsibility for further attacks, but this time identifying itself as the ‘Argirou’ Cell. While it is possible that a new cell had arisen in North Sulawesi, it is more likely that the same cell was keen to rebrand itself by adopting the name of another international anarchist prisoner. The cell’s namesake, Panagiotis Argirou, is a Greek anarchist of the Conspiracy of Cells of Fire group, jailed in 2010 for sending letter bombs to politicians throughout Europe.

The Sulawesi cell was by now deeply socialised into international FAI discourse and with great enthusiasm participated in the ‘ongoing dialogue’ between global cells. A number of statements even entirely abandoned references to local grievances. For example, a communiqué in January 2013 contains no mention of Kulon Progo or Bima (another land dispute previously frequently mentioned by anarchists). Not even Billy and Eat get a mention, despite having been released from jail only weeks earlier, on 22 November and 14 December 2012 respectively. Rather than local grievances, the communiqué offers salutes to foreign comrades, and brags of it radical ideals. ‘Last night we did it once again. Direct action based on our revolutionary values, as nihilists, as individualists and as an expression of the hatred of this society.’

It is unlikely that Indonesia’s anarchists have travelled to Europe, Latin America, or even in the region. Indonesia’s FAI is a lonely outpost of anarchist insurrection in Southeast Asia. Even so, the Sulawesi cell’s words are full of warmth and praise for their fellow revolutionaries overseas. Indonesia’s insurrectionary anarchists are increasingly consuming and replicating ideological trends of their European comrades. Six months after issuing their communiqué under the new name, the Sulawesi cell’s hat-tip to Argirou got a reply. Posting a letter on another international counter-info blog in June 2013, Argirou himself wrote ‘I have a special place in my heart for the comrades of the International Conspiracy for Revenge-FAI/IRF who burned a private vehicle in Indonesia’.

Ideology and strategy after Eat and Billy

The arrest, trial and imprisonment of Eat and Billy – and the discussions and literature produced as a consequence of their international stardom – is likely to have exposed many more Indonesian anarchists to international movements. But unlike their European comrades who have a long history of engaging fascist groups in open street warfare, it will be a long time before anarchists in Indonesia have the numbers or the courage for such attacks. But in a June 2013 statement, an Indonesian cell at least opened the door to such conflict in the future, stating that ‘the paramilitaries who were built by the military and have the same attitudes and behaviours like military are enemies who deserve our attacks.’ A Greek FAI cell recently claimed responsibility for bombing an office of the neo-Nazi Golden Dawn party ; attacks against groups like the Front Pembela Islam (FPI – Islamic Defenders Front) or Pemuda Pancasila (Pancasila Youth) by Indonesian cells would be a striking escalation of tactics.

The dearth of radical leftist groups in Indonesia robs anarchist groups of their natural anti-fascist allies. Yet at the same time, the absence of a thriving leftist scene grants Indonesia’s anarchists an unusually empty ideological space in which to thrive. Indonesian youths who feel alienated by urban life can find in anarchism a sophisticated and trendy critique of consumerism. For those who are more politically minded, anarchism offers a framework with which to critique oppressive state and social structures, from religious fundamentalism in Aceh, capitalist exploitation in Java, and military impunity in Papua. Anarchist ideas, in all their diversity and nuance, have much to offer Indonesia’s political and social activists, starved of ideology since the New Order regime tried to eradicate leftist ideas between the mid-1960s and late 1990s.

But their hostility to organisation might hamper them. Attempts at building mass followership, reads one Indonesian FAI communiqué, are ‘something which is inherited from the classical anarchist thought with a mixture of Marxism that is really disgusting’. Rather than bringing anarchism into the mainstream of radical politics, insurrectionary anarchism holds an inclination towards violence. The absolute rejection of movement building could even turn young Indonesians away from anarchism, stigmatise anarchism as a violent ideology, and trigger greater state repression against the wider anarchist community. While it seems that no injuries or deaths have been cause by insurrectionary anarchists in Indonesia so far, recent trends indicate that new cells are emerging and targets of arson attacks are diversifying.

On 31 March 2013 the FAI claimed responsibility for its first action in Aceh, where media reported that a ‘mysterious group’ burned down three buildings owned by Hamdan Sati, the head of Tamiang district. A communiqué described Aceh as ‘a region where religious fundamentalists in the past threw 64 punks into a rehabilitation camp’. But the statement went on to say that ‘we want to clarify that we aren’t Acehnese. We have no citizenship because we are borderless’. Between June and August 2013, cells claimed responsibility for fires at a karaoke bar in Jakarta, a clothing warehouse in West Jakarta and at a police school in Balikpapan, East Kalimantan. The claim of responsibility for the Balikpapan attack ends with a warning. ‘Our action is the direct revenge against pigs everywhere, not only in Greece. For every inch in your step that invades our freedom, we will hit you back more violent than before’.

Another sign that insurrectionary anarchism is growing in Indonesia is the appearance of entirely new groups. Between June and September 2013, the internationally active Earth Liberation Front (ELF) claimed responsibility for attacks on a car and shop belonging to the vice secretary of the Democratic Party in South Sumatra, arson attacks against ATMs in Makassar, sabotage of electricity stations in Jakarta, and setting fire to a factory in Bandung producing bullet proof vests. The communiqué states that ‘police must be attacked, as hard as possible’. Like the FAI, the ELF subscribes to an ‘anti-civilisation’ form of insurrectionary anarchism. On 20 August 2013, the ELF claimed responsibility for placing an incendiary device that burned out the third floor of the Institute Kesenian (Arts Institute) in the upscale central Jakarta suburb of Cikini, stating that artists are ‘the puppets of civilisation’.

As of September 2013, insurrectionary anarchists have claimed responsibility for arson attacks in Makassar, Bandung, Manado, Yogyakarta, Aceh, Balikpapan and Jakarta. But Indonesian police are increasingly determined to disrupt Indonesia-wide anarchist networks. In April 2012 four anarchists were arrested in Malang in possession of spray cans and solidarity posters for Billy and Eat. During interrogation lasting several days, police extracted information about which groups they belong to, their links to Billy and Eat, and how anarchist cells communicate with each other. Within days of these interrogations, an anarchist counter-information blog by the name of Memori Senja was taken offline.

But increasing harassment by police appears to have also led to a further radicalisation of a small group of insurrectionary anarchists. In an ‘open letter’ posted in September 2013, the Indonesian Section of the FAI revealed its most sophisticated and radical expression of ideology, goals and method. Billy and Eat’s arrest is described as ‘the starting point when everything became clearer for us’. In an escalation of rhetoric, the six-page text praises Indonesian Islamist groups for their the ‘brave choice’ in carrying out ‘violent jihad’, noting that forming informal cells of three to four people was key to the Islamists’ ‘success’. It passionately denounces the ‘social anarchists’ who reject violent methods, and it defines as legitimate targets ‘the human itself who stands at the side of the society’.

If insurrectionary anarchist cells keep multiplying, and violence leads to deaths or injuries, the police and media will start to pay much closer attention to anarchist ideology, and Indonesia’s harmless community of anarcho-punks could lose the relative freedom that they currently enjoy.

Dominic Berger (dominic.berger@anu.edu.au) is a PhD candidate at the Australian National University.

STOLEN FROM: https://www.cetri.be/Indonesia-s-new-anarchists?lang=fr